Data center operator Serverfarm repurposes data centers that are already up and running, but being operated by businesses that don’t need them. Original article by Scott Fulton III

Last week’s announcement from the El Segundo, California-based data center operator Serverfarm about its plans to add 14MW of capacity to its existing 80,000 square-foot Toronto facility, for a total of 21MW, would be an ordinary event in an ordinary time. But since we haven’t had “ordinary times” in what now seems like forever, the assertion that life and business do go on takes on a special significance.

“Adversity really, really releases creative thinking,” remarked Arun Shenoy, Serverfarm’s senior vice president for global marketing and sales, speaking with Data Center Knowledge.

“Doing it in the best of times is tough; doing it in such challenging circumstances is really tough.”

“We still managed to build a data center, which is a tough thing to do in the best of times,” Shenoy continued. “Nobody builds a data center slowly, and nobody says to us, ‘Take your time. If it takes you five years to build it, that’s okay, I’ll wait.’ No one has that level of patience, and rightly so. Doing it in the best of times is tough; doing it in such challenging circumstances is really tough.”

The Serverfarm growth model is somewhat different from that of most operators. Although it does build some facilities from the foundation up, in most cases it acquires existing properties that are usually owned and operated by private enterprises for their own purposes. These enterprises often built their own facilities during the heady, bonanza period of the 2000s, but then over-provisioned them in anticipation of a capacity growth forecast that ended up being unrealistic.

A 2007 report commissioned by the US Environmental Protection Agency projected that the nation’s total energy consumption by data centers would at least double by 2012. As things turned out, according to a February 2020 report researched by leading US energy scientists, global data center energy usage rose by only 6% between 2010 and 2018.

Reasons like this have enterprises everywhere coping with the consequences of choices they made back before the era of virtualization and lower-power processors. They have the overhead of running three or four times the data center they actually use, an added overhead that weighs even heavier during a global pandemic.

Serverfarm’s value proposition, which has been put to practice not only in Toronto but across the continent, is to acquire that overhead from these beleaguered organizations, which converts the former owners into Serverfarm customers and makes it their IT managers.

It also puts their old, excess capacity to use by way of leasing to other tenants. Many of its acquired facilities, Shenoy told us, were built to sustain 30MW of capacity, when all their owners actually utilize are around 5MW.

The next step in Serverfarm’s growth process is to build new capacity onto those existing complexes in calculated stages.

“Two things that we find very exciting about that model,” Shenoy said. “We can create capacity in very tight markets, very, very quickly. But the other thing … is, this is an incredibly sustainable way of building data center capacity. By definition, we’ve created 40MW in Toronto without the need to build a new building.”

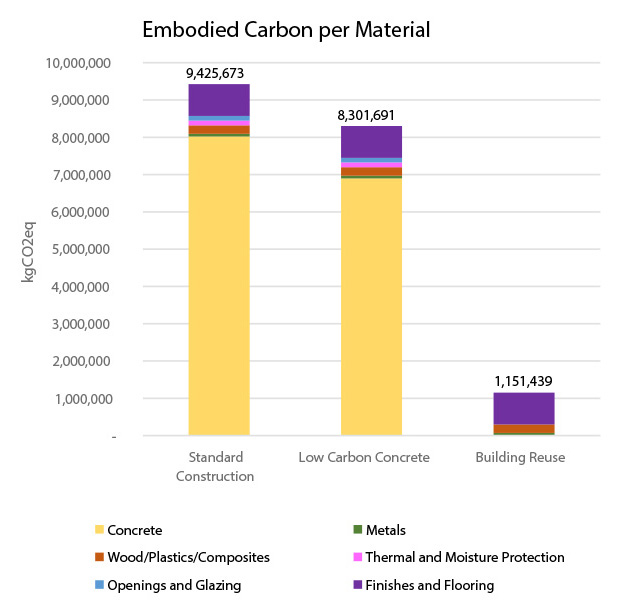

Put another way, the embodied carbon emissions incurred during a facility’s construction process have already happened. Serverfarm recently commissioned a study comparing the carbon emissions of updating its existing 38MW facility in Chicago against building a similarly equipped facility from the ground up. The upgrade emitted 88% fewer equivalent kilograms of carbon than the new project.

The graph shows the embodied carbon for the same building in three different scenarios. The first one is a standard new construction, the second is a standard new construction with a low carbon concrete, and the third is reusing an existing building. These scenarios are broken down per material, showing how concrete is the main contributor of embodied carbon in this case.

Granted, a new project would have added 38 more megawatts to the company’s total capacity, but it would have left underutilized capacity in the existing building, burning even more carbon for no good reason.

And as Shenoy argues, since Serverfarm didn’t have to pay for those additional emissions, neither do its clients. He estimates that if within the next three years, London-based customers were to demand 200MW of new capacity, it would be within Serverfarm’s capability to deliver it without constructing a single new facility there.

That’s not to say converting and repurposing old capacity in a pandemic isn’t challenging — especially in Toronto. Serverfarm VP for engineering and cloud, Sam Brown, told us the Canadian regulatory process makes builders jump through a few more hoops than in the US.

“For awhile there, we couldn’t do inspections in Toronto,” he said.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, nobody in the firm’s building department was free to come to the project site. Building permits took longer to process, and review times by law take 30 days minimum even without the pandemic. Also, self-certification, which is available to builders in the US for ensuring sustainability targets are being met, is not an option in Canada.

Instead, Serverfarm’s facility engineers produced the documentation needed for third-party inspections, including using seat-of-the-pants virtual techniques developed with the assistance of partners and vendors.

“The engineers are every bit as detailed as an inspector, if not more, when it comes to implementation of work in the field,” Brown said. “There were issues. It’s not like these things were surface reviews. There were some hard conversations we had to have, and the issues were being raised from people inside the team.

“It was tough this round,” he added, “but now that you know what all of the expectations are, you can cater to them and make sure you’re not over-promising and under-delivering.”